I’ve been thinking a lot about bird migration. Each fall, migratory birds traverse city, country, and even continental borders as they fly away from winter and toward a more hospitable climate. In the spring, the land calls them back to where they were born and they return to nest. I was born in Texas and migrated to Boston two years ago, and every winter I feel a reliable pull to fly back down south, seeking the solace and familiarity of home. Like the migrating birds, I journey back and forth with the seasons.

I’ve never been one to adapt quickly to change, and I’ve struggled to find my footing in a new city. Everything feels unfamiliar and I keep walking to the wrong beat, slipping from apartments, careers, and relationships in an effort to find solid ground: something consistent that feels real and lasts. I moved to Boston with a long-term partner who promptly became my first real lesson in saying goodbye, and afterwards, I remained in the city, untethered. The landscape, culture, and weather in the Northeast couldn’t be more different from what I’m used to, and sometimes I think that I am the air floating through the streets, unperceived and unattached to any one place or feeling.

My first recording of a Northern Mockingbird in Austin

The first time I felt at home in Boston was on a hot summer day, when I heard the unexpected but familiar voice of a Northern Mockingbird booming from the top of a lamppost. Northern Mockingbirds fill my neighborhood back home in Austin with a cacophony of imitations of other birds, frogs, and car alarms. An unassuming grey bird with discerning yellow eyes, they were one of the first birds I ever identified, and I proudly recognize them as my “spark bird”, or the species that sparked my interest in birding. This particular mockingbird may have migrated back up to the Northeast during spring migration, and it was the first truly familiar face I’d encountered in a while. Soon after, I signed a lease to stay in Boston for another year, abandoning my plans to move back down south.

Since then, I’ve learned to orient myself using the wildlife around me, and the reliable flux of bird migration with the changing seasons provides much-needed familiarity. After two years here, I’m getting the hang of the timing. Each fall, I look forward to the following itinerary:

- Send off certain birds once the leaves start changing — See you next year, Wood Duck!

- Rush to trails at sunrise to catch a glimpse of those stopping by from further north on their way to Mexico and beyond — Good luck, Blackpoll Warbler, and feel free to stay here awhile!

- Welcome those who decide to move in for the winter — Welcome back, Dark-Eyed Junco!

On the other side of the cold season, I eagerly anticipate the return of those coming home to breed and thank the skies that they made it back safely. There is a rhythm to it all — a grounding — and I’ve settled into it. I meet the wintering birds with curiosity and warmth, greet the returning spring migrants like old friends, and repeat. I know where to find them (and they me), and whether or not they arrive, I’ll be waiting to welcome them back.

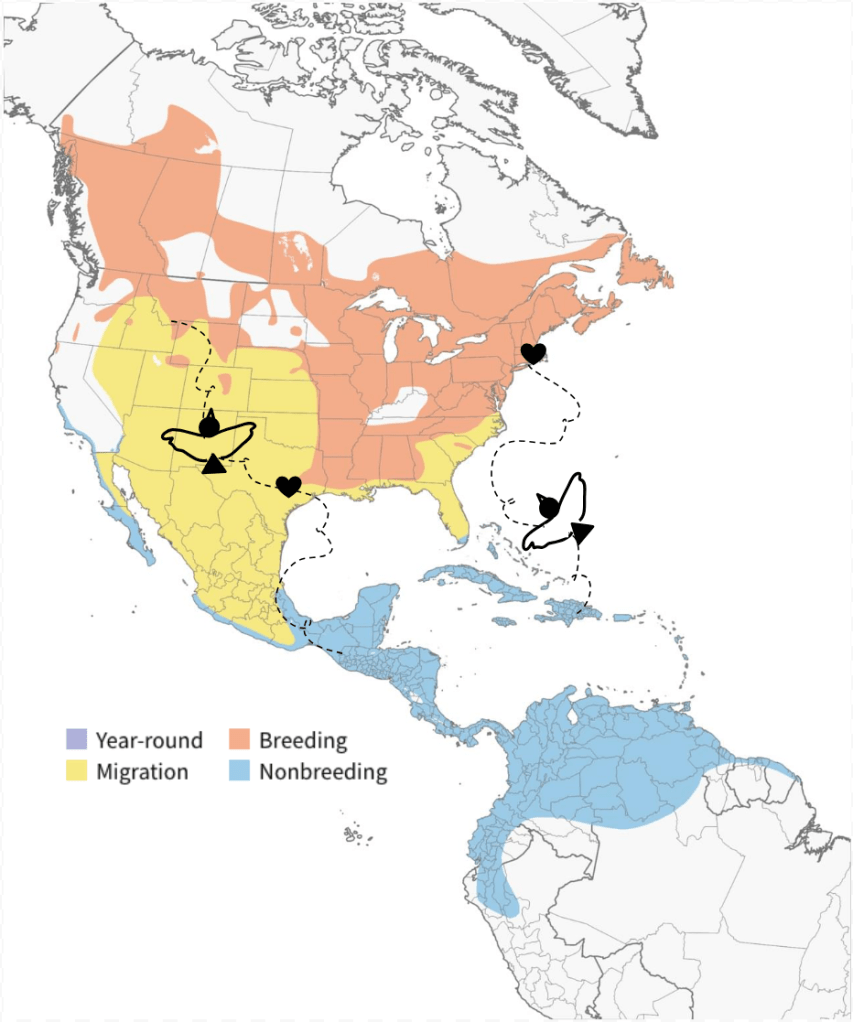

Bird migration is perilous beyond what I can imagine; my own migrations are facilitated by comfortable trains, cars, and commercial airlines. Migrating birds can venture thousands of miles through dangerous conditions, fueled by limited sleep and food. In some migratory species, more than half of deaths occur during migration. So when I hear a Baltimore Oriole warbling in the spring, recently arrived in Boston from Colombia to nest, I am awed by all that they must have learned, endured, and overcome during their travels. I picture the rising and falling terrain they observed from above; the crickets, snails, and berries they sampled between mile 20 and mile 2,000; the brilliantly violent thunderstorm they took shelter from alone in an unfamiliar wood. Perhaps they even rested one evening in the greenbelt behind my house in Austin and took comfort in the steady chorus of crickets and Chuck-Will’s-Widows, just like I do when I’m there. I wonder what they made of everything they saw during their journey, and which experiences will stay with them forever as lessons for next year.

My first recording of a Baltimore Oriole in Boston

Unbearable and rising summer temperatures in my hometown in Texas helped prompt my migration to the Northeast, and it comes as no surprise to me that climate change impacts bird migration as well. Some species respond to warming temperatures by shifting their breeding and wintering ranges further north; I will delight in welcoming newcomers to Massachusetts, and will grieve the absence of familiar voices and songs when I return back home to Texas, alone. Birds in mountainous areas are responding to warming temperatures by climbing up to higher altitudes and cooler temperatures, leaving behind what’s familiar and reaching for the heavens until they run out of solid ground and can ascend no further. Some researchers refer to this ascension as an “escalator to extinction”.

The beat is changing. As temperatures rise earlier in the year, insects hatch earlier and out of sync with bird migration timings. After an arduous journey north to their breeding grounds in the spring, some birds arrive home, exhausted, only to discover that the insects they rely on for food are scarce or unavailable. I imagine walking from Texas to Massachusetts without having eaten a single meal, and then arriving, exhausted, only to discover that everything in my fridge has spoiled.

In addition, climate change has increased the frequency of false springs, which wreak havoc on an ecosystem from its earthbound creatures up to those in the skies. During a false spring, sudden, extreme cold spells interrupt sustained warm temperatures and destroy existing vegetation and other food sources for birds. These sudden freezing temperatures can kill the exact birds that ventured south expecting safety. I picture traveling home to Texas for the winter, looking forward to food, family, and warmth, and being met with the door slamming in my face.

Birds are remarkably resilient, and some species adapt their migration tactics to survive and thrive in a warping climate. For example, the American Redstart (an agile, Halloween-colored warbler with a flashy tail) has increased its spring migration speed to accommodate for a delayed departure caused by deteriorated habitats and shortened food availability in its breeding grounds. There is power in changing behaviors innate to you — those behaviors that you were born with and that your blood compels you to perform — when they no longer serve you. This is something I am still learning to do as I embrace change in my life, and I look to these birds for guidance.

However, you can only change your nature so much, and some adaptations come at a cost. When birds speed up migration by flying faster and taking fewer breaks to refuel, it can be fatal. In addition, some species simply cannot adjust their migration patterns to survive climate change. Shorter distance migrants whose destinations more closely resemble their origins can respond to local weather changes and shift their migration accordingly. However, longer distance migrants have a more fixed migration rhythm and may rely on changes in daylength to trigger their departure. They cannot anticipate false springs or inhospitably warm weather in a destination thousands of miles away, and must trust that their instincts will not betray them. When they do manage to adjust, they suffer in new ways. The American Redstart, a long-distance migrant, has paid for its accelerated migration with a sunken survival rate.

I am left thinking of those birds we leave behind: casualties of climate change who cannot change quickly enough and are left flying out of rhythm, out of time. For how many more seasons will I get to welcome them home? How do I mourn those who fly down south and do not return in the spring?

fare thee well little bird

may stars bright guide you true

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

some luck / some skill

will bring you back / to inspire me / once again.

J. Drew Lanham

I am not an ornithologist by training, but my heart belongs to birds. I grieve the loss of species, and the loss of a single migratory bird, like I grieve the departure of anyone dear from my life. I am lost without them, and I don’t know how many more goodbyes I can take. I know that two-thirds of North American bird species are at increasing risk due to climate change; that drought, fire, and rising sea levels are destroying birds’ nesting areas and habitats at alarming rates; that compensating with a delayed and rushed spring migration is neither sustainable nor a burden that the world’s migratory birds should have to shoulder.

But I don’t think in numbers, percentages, or sea levels, and as I practice staying present with uncertainty in all aspects of my life, I’ve decided to spend less time ruminating over the future of climate change. It separates me from the living, breathing connections I have with the natural world around me, with the land and all the species I encounter. I know that not all birds will stay, but if I grieve their loss in advance, I will grieve twice. Love is a decision, and I have decided to love them today and tomorrow, while I still can, in the time we have left together. So I will continue to move in rhythm with the migrating birds around me and complete my own migration, and each time I return to Boston, I’ll hold my breath that they will, too.

Chuck-Will’s Widows calling from my backyard in Austin

Leave a reply to Elaine Olund Cancel reply