A grassroots effort to save nightjars shows that the future of conserving elusive birds depends on citizen science.

Note: I wrote this story for a class assignment in MIT’s Graduate Program in Science Writing in December 2025.

Most people associate birdsong with the daylight hours. But if you step into a forest, scrubland, grassland or desert on a warm, moonlit summer night, you might hear the chant of a nightjar—a small, heavily camouflaged, reptilian-looking bird that sings more when the moon is bright.

That’s exactly what happened to Logan Parker while birdwatching one evening in western Maine. He heard the call of an Eastern Whip-poor-will, a nocturnal bird in the nightjar family, and fell in love. But while they were once ubiquitous, nightjars are sharply declining across the continent, and the nights are getting quieter without their calls.

While conservationists believe that nightjar populations are dramatically falling, the birds are notoriously elusive, making it difficult to quantify their decline and pinpoint its causes. After learning that Eastern Whip-poor-wills are declining across their range, Parker launched the Maine Nightjar Monitoring Project to gather more data and learn how to protect them. His volunteer-driven project has revealed critical insights about nightjar migration and shows that the future of saving elusive birds depends on citizen science.

“Everyone that was familiar with these birds was now saying, hey, we’re not hearing them anymore,” said Parker, an ecologist at the Maine Natural History Observatory. “Nightjars seem to conjure a lot of nostalgia in people, given they’ve declined as much as they have.”

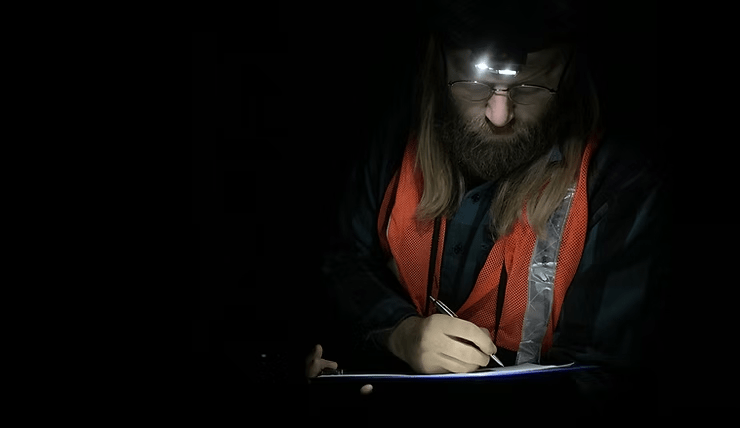

Parker and one other volunteer began conducting nightjar surveys in Maine in 2017, driving routes through nightjar habitat and stopping to record observations of the birds. The project has since grown to approximately 40 volunteers — and helped spark the creation of the Global Nightjar Network — and it is still largely volunteer driven, with citizen scientists signing up to cover routes across the state during nightjar breeding season in the summer. Because nightjars are so difficult to find, there simply wouldn’t be enough people on the ground to collect data without volunteers.

“Nightjars are as still as a rock — they look like rocks, they look like sticks, they look like leaves,” said Gretchen Newberry, a biologist and author of “The Nighthawk’s Evening.” “They look like whatever they want to look like, and you can walk right by them.”

Nightjar surveys require a strict alignment of timing, moonlight, and suitable weather, and volunteer availability is critical. It would be too expensive to employ technicians and biologists to conduct the surveys, and Parker was only able to collect the data he needed about nightjars because he could send volunteers out all over the state.

Without volunteers, he would have had to rely on autonomous recording units (ARUs), tools that monitor wildlife acoustically. But ARUs generate a massive amount of information that he would then have to analyze, and they’re missing a necessary human element.

“ARUs can’t be responsive to things on the ground in the way a volunteer can, and we lose the benefit of having community members involved in this science and developing their own relationship to these birds, which I think is really important,” he said.

Contributing to the Maine Nightjar Monitoring Project has inspired some volunteers to take initiative to save other birds and wildlife, leading to a snowball effect of positive conservation efforts.

“Volunteering made me appreciate the nighttime animals better,” said Kshanti Greene, a volunteer in West Gardiner, Maine. “During my five years doing survey routes, I’ve gotten more involved with wildlife overall.”

Greene first started doing survey routes for the Maine Nightjar Monitoring Project with her husband in 2020. She now runs the Maine Birds Facebook group, where people discuss wild birds and share sightings. She also conducts independent data science research to study grassland birds using their calls and volunteers doing wildlife rehabilitation.

“You just can’t afford to hire enough field scientists to do that work,” Greene said. “Getting people involved is a huge deal, and the more information and education you can get out about these animals, the better.”

Volunteers for the Maine Nightjar Monitoring Project also helped attach small radio nanotags to Eastern Whip-poor-wills and Common Nighthawks — another species of nightjar steeply declining across the continent — to track them during their migrations.

By tracking nightjars as they migrate from Maine to their non-breeding grounds thousands of miles away in Mexico and South America, Parker has learned that Eastern Whip-poor-wills stay in their Maine breeding grounds long after they’ve stopped singing and into early October — about one month longer than previously thought. This insight could help inform land managers, who often start thinning vegetation and doing prescribed burning in the fall under the assumption that the ground-nesting birds had already left.

“People often think that all migratory species move at the same time, but certain species can stay longer than you’d think,” Parker said.

The nanotags have also revealed that Eastern Whip-poor-wills from across the eastern US and Canada all converge in one highly developed area in East Texas, creating a risky bottleneck for resources and collisions. Parker hopes to work with researchers through the Global Nightjar Network to recommend lights out and habitat maintenance projects in East Texas to support the birds as they fly south, ensuring that they have people watching over them every step of their journey.

Nightjars are sensitive to development, and their habitat is declining and degrading throughout much of their North American range. Climate change is also shifting their populations, with Eastern Whip-poor-wills expected to move out of the southeastern US and concentrate more heavily into Maine. Parker is worried that the state doesn’t have enough suitable habitat to sustain the changing population.

“At a certain point, they’re going to be squeezed off the landscape,” he said. “But they’re quite resilient, too, in that they’ve seemed to have endured for so long.”

People are starting to realize that there are nightjars around, and that they may have even been hearing them without realizing it, which makes them want to become involved in conservation efforts, said Newberry. She thinks that nightjars need extra attention that they aren’t getting because they’re nocturnal, so she spends much of her time talking about her book and about nightjar conservation. She’s not ready for the nights to become quiet without nightjar calls just yet.

“I want to talk about them a lot because before you know it, things just disappear in the dark,” she said. “We don’t know that they disappear if they are hidden from us.”

Leave a comment