With bird populations in steep decline, weather radar provides insights into when and where birds migrate and how to prevent collisions.

Note: I wrote this story for a class assignment in MIT’s Graduate Program in Science Writing in November 2025.

If you looked at the moon through binoculars on the night of October 8, you may have seen flocks of birds flying across it. These would make up a small fraction of the 1.25 billion birds that migrated across the continental United States that night, marking the largest night of migration in recorded history.

A combination of weather patterns, timing, and climate change led to the massive night of migration. After a cold front passes, winds shift to blow toward the south and southeast, giving North American birds a boost as they migrate to warmer regions. A large cold front moved through the western Great Lakes region and upper Mississippi River around October 8, and a break in storms enabled birds that had been waiting to migrate to take flight — conditions that happened to converge during peak fall migration season.

Climate change and habitat loss due to humans are making migration patterns like these particularly intense, with recent wildfires in the boreal regions of Canada likely contributing to the record-breaking night.

“It was the opposite of a perfect storm — a perfect calm, when the storms had passed and the birds were moving,” said Andrew Farnsworth, a biologist at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology who works on the platform BirdCast, which tracked the massive night of migration.

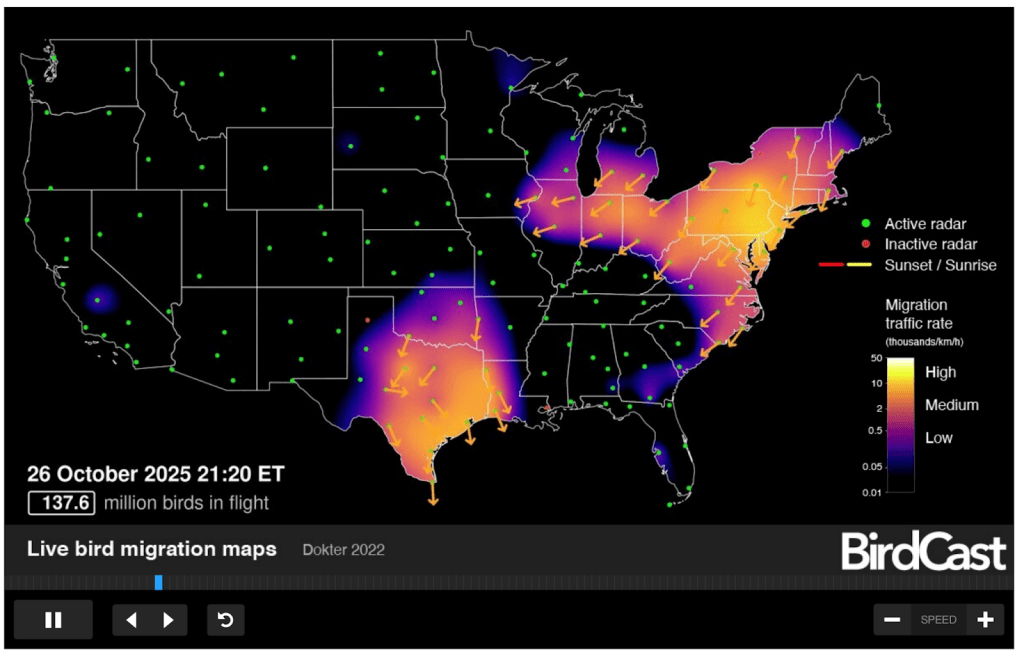

BirdCast is a science-based collaboration between the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Colorado State University and the University of Massachusetts Amherst that was launched in 1999. The platform uses weather radar to count and predict how many birds migrate on a given night, and displays this information in live migration maps and dashboards, illuminating a nighttime phenomenon that would normally be hidden to human eyes.

Research groups and universities around the world use radar technology to study bird movements, but BirdCast is the only platform in the US doing so publicly with weather radar. Bird populations across North America are in steep decline, and weather radar provides insights into large-scale bird migration that can inform conservation efforts and reduce collisions. More than a billion birds in the US die each year from collisions with buildings, and the stakes are even higher during massive migration nights like on October 8.

“If you can imagine that three times the US population was migrating and moving in one direction one night, that’s what this night would be like,” said Farnsworth.

BirdCast uses Next Generation Weather Radar (NEXRAD), a system of Doppler weather radars throughout the US, to track birds in the air. NEXRAD radars emit radio waves and measure how long it takes for the waves to bounce off of an object and return, as well as the strength of the returning waves. Through this data, it can determine where objects are, their densities, and how fast they’re moving relative to the radar site. When meteorologists use NEXRAD to track weather systems, they ignore data from smaller objects, like birds. That’s where BirdCast steps in.

“We biologists look in the garbage can of the meteorologists,” said Adriaan Dokter, a biologist at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology and BirdCast.

BirdCast uses NEXRAD data to separate stationary objects, like buildings, from moving birds, enabling the system to detect entire flocks of birds, but not individual birds.

“It’s more like density blobs in the air, and then we convert that into bird numbers,” Dokter said.

To estimate the number of birds, BirdCast divides the total biomass in the air by an average songbird size of 11 square centimeters. Smaller birds usually migrate earlier in the season than larger birds, so the system probably underestimates bird numbers at the beginning of the season, and overestimates them at the end, but it gives a pretty good sense of the overall numbers, Dokter said.

Understanding bird migration is important to prevent collisions with manmade objects, like buildings and airplanes. Weather radar gives scientists a unique opportunity to pinpoint exactly where in the sky large flocks of birds fly to inform decisions around constructing new buildings and promoting lights-out periods.

“It’s amazing that we have this network of radars that continuously monitor the sky and see everything that’s going on,” said Cecilia Nilsson, a behavioral ecologist at Lund University in Sweden. “You can use GPS to track individual birds, but there’s no other method that can give you those large scale patterns.”

Nilsson uses weather radar to study the range of altitudes birds use when migrating. She wants to understand where birds are in the sky and how readily they can shift to different altitudes in order to inform decisions about where to fly airplanes and drones, and where to build skyscrapers and wind turbines.

Back in the US, BirdCast is collaborating with the Bird Collision Prevention Alliance to promote glass treatments, lighting practices, and collaborative action to reduce collision fatalities during migration. Scientists like Farnsworth and Dokter also use observations from citizen science platforms like eBird to improve BirdCast and better understand migration, so it helps when everyday people go birding and report what they see.

“This is one primary example where the observer is really critical,” said Farnsworth. “The basic birding that you do, whenever and wherever you do it, is really important.”

Leave a comment